The Lucid Motors Configurator is A Video Game Streaming to Your Browser

It makes sense when you realize video game engines are the best simulators out there.

A Clever Solution

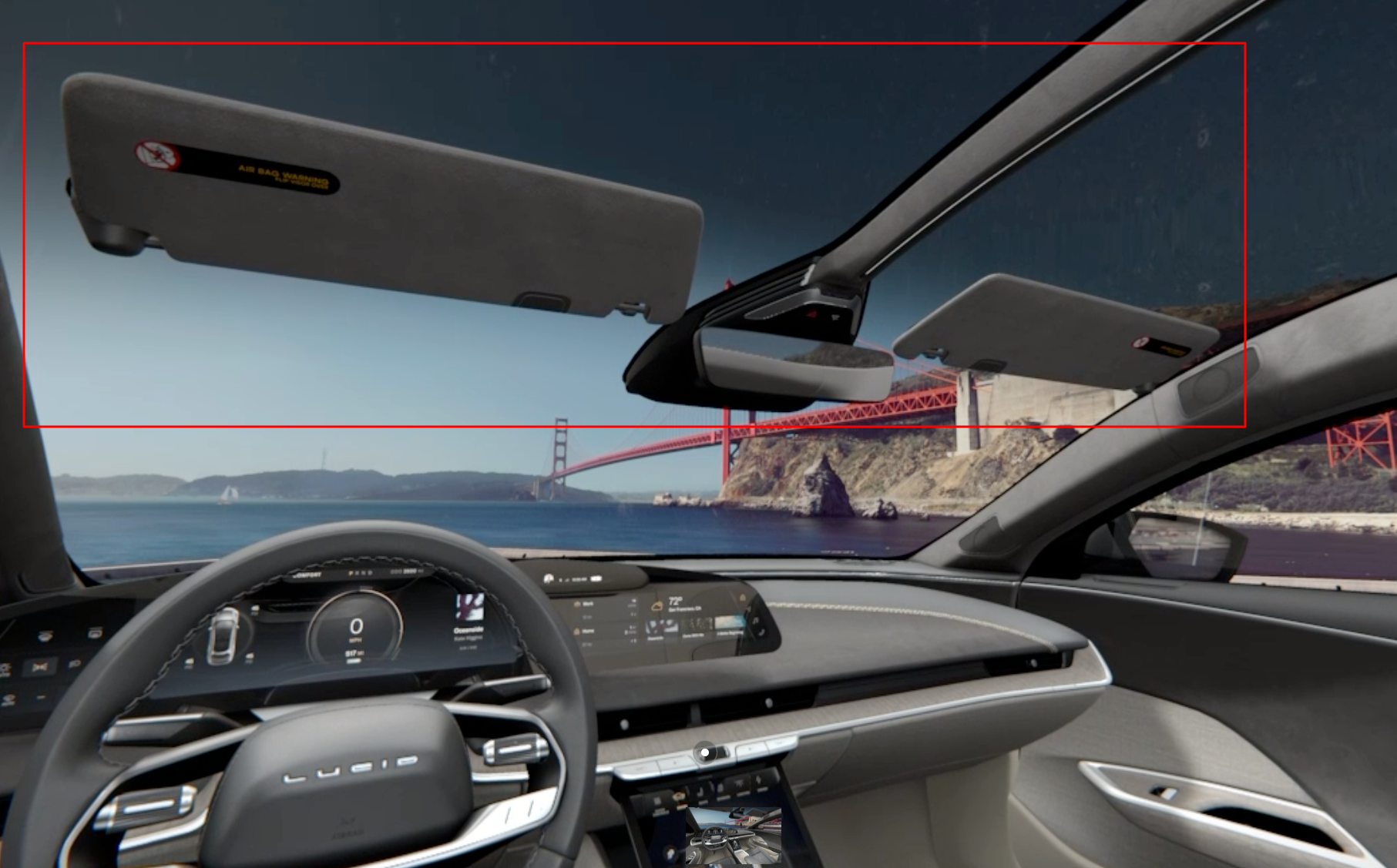

Lucid Motors went public on Monday, and although I am not going to be buying a Lucid anytime soon, I found myself looking at their vehicle configurator out of curiosity. It is a piece of art. It allows you to observe and interact with the vehicle from almost every direction, inside and out:

Lucid's configurator for their flagship elite vehicle, the Lucid Air Dream.

You can simulate various colours and trims, open and close the doors, and even retract the center console display. The backdrop of the Golden Gate bridge reflects off the glassy puddles. The configurator preserves all sorts of details of the vehicle, including lights under the door handles that activate when you are using them. I feel like I got an accurate enough feel for the vehicle, I don’t even have to see it in person anymore.

So how did Lucid manage to pull this off? Can you expect the average user’s web browser to render a scene like this in real-time, reflections and all? The answer is probably not. It works because the scene you are seeing is rendered with Unity, a video game engine, running in the cloud - offloading the intense computational load to an Amazon server - and streamed back to your browser via WebRTC - a peer-to-peer video streaming protocol.

The Model

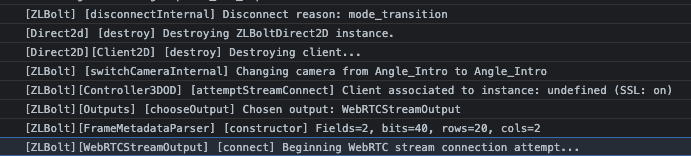

Initially, I naively assumed that the model was being rendered in my browser via the latest WebGL library (an API for rendering 2D and 3D graphics in web browsers with hardware acceleration). And since the model must have been rendered locally, it had to exist in my RAM somewhere, so I could extract it and load it up in a 3D model editor. Specifically, I wanted to see if I could remove the sun visors interrupting the almost seamless glass canopy - an effect achieved by Tesla’s Model X, I’m not sure why Lucid didn’t follow.

Lucid Air sun visors interrupting the glass canopy.

So I dove into the code. After some time with the browser debug tools, skimming thousands of lines of minified Javascript, recording and examining the network requests between my laptop and Lucid’s servers, I realized the answer was quite literally just being printed in the console the whole time:

The Configurator is a webRTC stream.

There’s no local model being rendered. What I’m seeing is a video.

So what’s happening here? The configurator initializes with a 2D display - that is, a choppy panorama of images which provide the illusion of a 3D interaction. This is how most online interactive 3D displays are constructed. You can see a demo of that below:

A choppy 3D view, created by a series of 2D images.

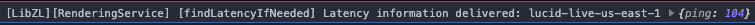

Then, the client tests my bandwidth and latency, and if it’s fast enough to support a realtime video feed, it upgrades the session to 3D:

You upgrade to a 3D session if you have the bandwidth.

This initiates a webRTC connection. WebRTC is a peer-to-peer streaming protocol. The scene is rendered elsewhere, and streamed via webRTC to my browser.

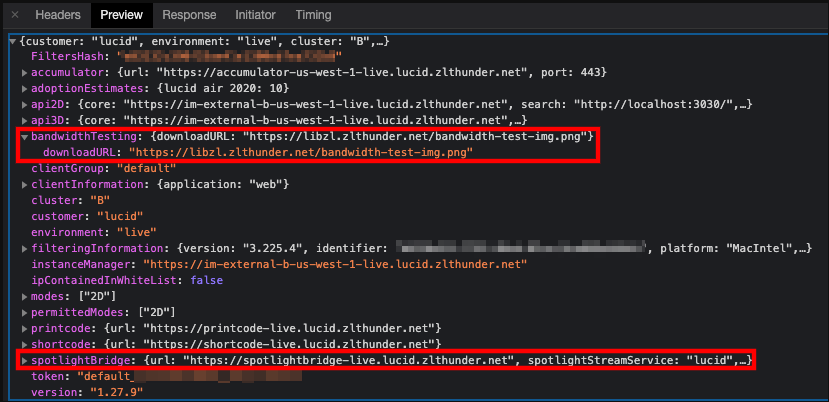

Inspecting the contents of their get_token request reveals some more details about their mechanics.

Contents of the get_token request.

The first box reveals that, to test your bandwidth, they partially download from a 25 MB test image to your device, and time how long that takes. This is the image, if you’re curious (don’t worry, I’ve compressed it down 10x).

Doesn't have much to do with automobiles, but it will test your bandwidth just fine.

By the way, this image seems to be an effect produced by the plasma plugin from GIMP. It loads quite slowly; as it resembles noise it must be largely incompressible.

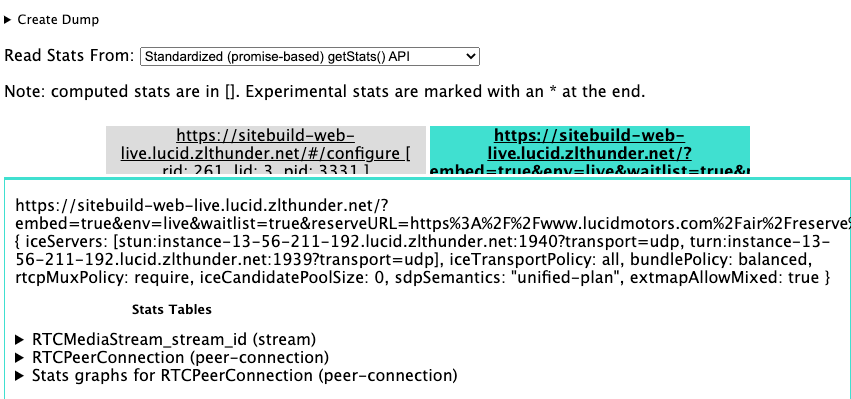

Opening up chrome://webrtc-internals/ reveals some details about the webRTC connection streaming the 3D scene to my browser.

Chrome's debug tools provide more information about the webRTC connection.

At this point, you may have noticed that none of the URLs here are on a lucid domain, but rather under zlthunder. Who are they?

ZeroLight

Searching the web for zlthunder brings you to a company called ZeroLight. They indicate that they provide cloud-based 3D visualization, specializing in automotive. It all makes sense now!

Cloud based 3D visualization specialists.

It wasn’t much longer until I found this blog post from Unity (the prominent video game engine) explaining how ZeroLight leveraged the engine to create a realistic virtual showroom, with optimized physics, reflections, and all.

Video games have brought us a long way.

Now I put all the pieces together. When I connect to the site, they load a 2D configurator. If my internet connection can handle it, they connect me to an instance of Unity - a 3D video game engine - running on an AWS server. The server receives my mouse inputs, rotating and zooming the field of view, renders the results in the cloud, and streams them back to me.

Sounds Expensive

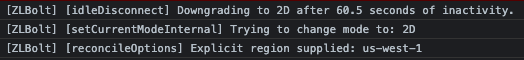

Imagine you have a 1,000 users connected to the site: you need a 1,000 hardware accelerated instances of a video game engine receiving inputs and streaming back large amounts of realtime video- just like the cloud video games products that are Stadia and GeForce Now, among others. But it seems they’re very aware of that: to save on costs, they disconnect you after 60s of inactavity:

Downgrading on idle must save a lot of money.

What is a Video Game Engine Anyway?

Although it may seem a surprising use of a video game engine at first, a video game engine is really just an optimized simulator. Established game engines like Unity incorporate decades of research into simulating light rays and other physical phenomona. So if you want to simulate reality, even if that reality is a showroom, a video game engine is a perfect, ready-to-use tool, that can be extended to many applications.

In hindsight, I probably could have figured out how Lucid’s configurator worked by doing some searching and coming across the article from Unity. But reverse-engineering the configurator provided a closer look inside the challenges, solutions, and mechanics of their product, and I felt like a detective working from the ground up. What I found most amusing, though, was the incredible complexity we have achieved in technology today. A super realistic physics simulator, running on a remote server in an Amazon data center, receiving commands from my computer and streaming back the video feed at the speed of light, so that I can play with a car configurator. And all we needed to get to the moon was a calculator!